Testing

#

Tests can be seen as a runnable documentation of your code. Automated testing gives you confidence to change the code. Manual testing is the other end of the spectrum. It’s also the most labor intensive and brittle option.

What to Verify With Testing

#

Testing can be used to verify at least the following:

- Do parts of the system work in isolation?

- Do parts of the system work together?

- Does the system works fast enough?

- Does the old API of the system still work for the consumers?

- Do the tests cover the system well?

- What is the quality of the tests?

- Does the system solve user problems?

You can test both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Qualitative testing is harder as it requires a comparison point, but without tracking quality, such as performance, it’s difficult to reach it. If you track how the system is being used and capture analytics, you can tell how the users experience the system.

Develop the Right System the Right Way

#

A technically correct system may not be correct from the user point of view and the other way around.

Popular projects put a lot of effort into the façade encountered by their users. This has led to techniques such as defensive coding. A good API should fail fast with a descriptive message, instead of swallowing errors.

How Much to Test

#

Regardless of how much you test, manual testing may still be required, especially if you target multiple platforms. But it’s a good goal to minimize the amount of it and even try to eliminate it.

No matter how much you test, problems may still slip through. For this reason, it’s good to remember that you get what you measure. If you want performance, you should test against performance. To avoid breaking dependent projects, you should test against them before publishing changes.

Tests come with a cost. Test code is the code you have to maintain. Having more tests isn’t always better. Put conscious effort into maintaining good tests instead of many. Fortunately, tests allow refactoring and sometimes finding better ways to implement the desired features can simplify both the implementation and tests.

How to Test Old Projects Without Tests

#

In older projects that have poor test coverage, tests can be used for exploration. Explorative testing allows you to learn how the code works by testing it. Instead of running the code and examining it, you can write tests to assert your knowledge. As you gain confidence with the way the code works, you are more willing to make changes to it as the risk of breakage decreases.

Specific techniques, such as snapshot testing or approval testing, allow you to capture the old state of an application or a library and test against it. Having a snapshot of the state is a good starting point as then you have something instead of nothing. Capturing this state is often cheap, and such tests can be complemented with more specific ones. They provide a baseline for more sophisticated testing.

Types of Testing

#

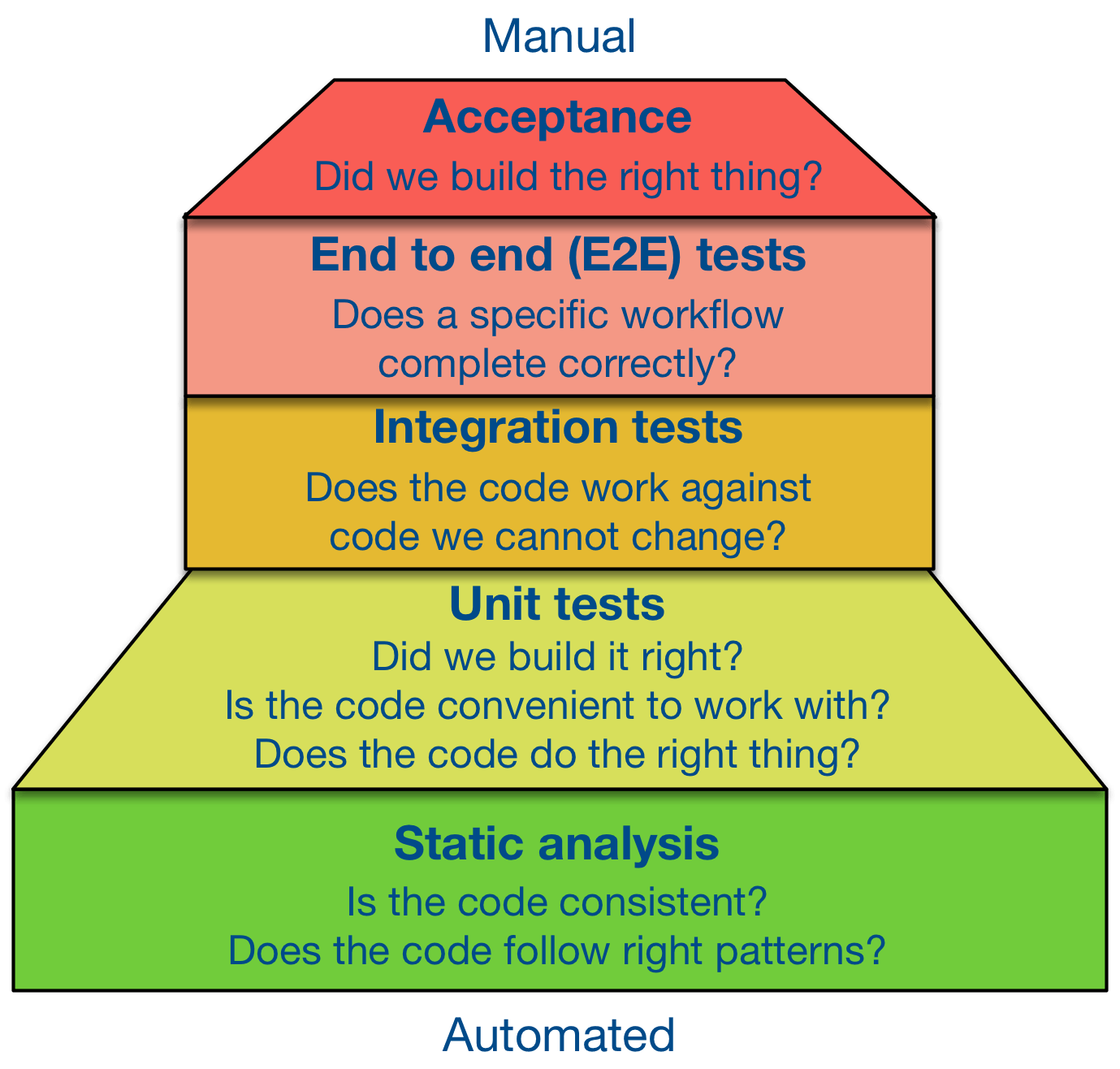

Mike Cohn popularized the concept of the test pyramid↗. He split testing into three levels: unit, service, and user interface. The test tower adapted from his and Forbes Lindesay’s work↗ expands on the idea.

Each type of testing provides specific insight to the project. The following sections cover the most common techniques while also discussed a few beyond the tower.

Acceptance Testing

#

Acceptance testing looks at testing from the user perspective. It answers the question can the user complete his tasks using the app UI. Tools like CodeceptJS↗, Intern↗, or Selenium↗ provide a high-level syntax that allows you to model user behaviors, and run tests in a real browser.

End to End Testing

#

End to End testing (E2E) is closer to technical level than acceptance testing and tests particular use flows. For example, in an application you would test that the user can log in and log out. Or that the user can fill a form in a specific view and get expected results.

Tools like puppeteer↗, TestCafé↗, Nightwatch.js↗ and services such as cypress↗ focus exactly on this type of testing.

Integration Testing

#

Integration testing asserts that separate modules work together. You can use the same ideas as above except that the scope of the system under the test is smaller.

Unit Testing

#

Unit testing asserts modules (units) in isolation. You can get started by using Node assert↗. Specialized assertion libraries have more functionality and better output but assert is a good starting point.

To have something to test, define a module:

add.js

const add = (a, b) => a + b;

module.exports = add;

To test the code, create a file that imports your module and run assertions against it:

add.test.js

const assert = require('assert');

const add = require('./add');

assert(add(1, 1) === 2);

If you run node add.test.js, you shouldn’t see any output. Try breaking the code to get an assertion error.

Jest↗, Mocha↗, AVA↗, and tape↗ are the most popular test runners — you don’t have to do this work yourself.

It’s good to understand that unit tests cover functionality from the developer perspective. These small assertions can be used to define a low-level API. Test Driven Development allows you to shape the implementation as you figure out a proper specification for your API.

Property Based Testing

#

Property based testing asserts specific invariants about code. For example, a sorting algorithm should return items sorted in a specific order. This fact is an invariant and should never change.

When invariants, like the sorting one, are known, it’s possible to generate tests against them. Property based testing can find issues unit testing could miss, but the invariants can be hard to find.

To continue the previous example, a property based test could be used to show that add is a commutative operation. Commutativity means that swapping the parameters should still yield the same result so that the result of a + b should equal b + a.

add.property.test.js

const assert = require('assert');

const add = require('./add');

// Test an invariant once

testProperty(

[generateNumber, generateNumber], // Test against numbers

(a, b) => assert(add(a, b) === add(b, a)) // Commutativity

);

function testProperty(generators, invariant) {

return invariant.apply(null, generators.map(g => g.call()));

}

function generateNumber() {

return Math.random() * Number.MAX_VALUE;

}

If you run the test, it should pass given add is a commutative operation. The same idea can be applied to more complicated scenarios. There are a few improvements that could be made:

- Instead of running a single test, run

testPropertymany times with different values. You could model this astestProperties(<property>, timesToRun). - The test generates random values without allowing the user to set the seed value. This is a limitation of JavaScript API. To keep the tests reproducible, it’s a good idea to replace

Math.randomwith an alternative that allows you to control the seed. - Replace

testPropertyandgenerateNumberwith existing implementations from npm. - If the

addfunction contained type information, it’s possible to extract that and then map the types to generators. Doing this would keep the test code slightly neater if you have multiple tests as then you would have to define the mapping between types and generators in one place while individual tests could skip the definition problem.

Property testing tools like JSVerify↗ or testcheck-js↗ are able to shrink a failure so you can fix it. The biggest benefit of the technique: it can help to discover boundary cases to repair.

Static Analysis

#

Static analysis tools, such as ESLint or Flow, can help to keep code consistent and push it towards right patterns. They could be great low-maintenance addition to tests, as discussed in the Linting and Typing chapters.

Security Testing

#

Security testing addresses vulnerabilities that allow a potential attacker to breach a system.

npm checks packages for known vulnerabilities on every install, npm audit fix↗ upgrades ones that have no breaking changes. It’s a good way to keep your project secure without spending too much time upgrading dependencies.

eslint-plugin-security↗ identifies potential security hotspots that need to be checked by a human.

Regression Testing

#

Regression testing makes sure the software still works the same way as before without breaking anything.

Approval testing allows you to develop regression tests against an existing system. The idea is to store the existing system state as snapshots and use this data for testing a behavior for changes while the implementation is being refactored.

Visual regression testing allows you to capture the user interface as an image and then compare it to a prior state to see if it has changed. If it has, then the failing test needs validation by a developer to make sure the result is still acceptable. Semi-automation like this is valuable especially if you have to support multiple environments and devices.

Regression testing applies on API level as well. An API that has worked in the past should work the same unless the API contract changed.

Performance Testing

#

Performance testing is valuable for projects where speed is important. Packages like k6↗, Benchmark.js↗ and matcha↗ can be helpful here. You can benchmark your implementation against competing libraries or an older version of yours.

Ideally, you should store the old results somewhere and keep the runtime environment the same across separate runs. If the environment varies between runs, benchmarking results aren’t comparable. Assuming you are using a conventional Continuous Integration (CI) server without storing the performance data somewhere in between and cannot control the environment, you can run both the older and the current version of the system during the same run to detect performance regressions.

Performance testing also yields insight into different environments, and you can test against different versions of Node for example. The same point is true for other forms of testing.

Mutation Testing

#

Mutation testing allows you to test your tests. The idea is to introduce mutations into the code under test and see if the tests still pass. Tools like Stryker↗ enable the technique for JavaScript.

Package Testing

#

To make sure your npm package paths, like main or module, work, test your package with pkg-ok↗.

Code Coverage

#

Code coverage tells you how much of the code is covered by tests. This can reveal parts of the code that aren’t being tested. Those parts have unspecified behavior and as a result may contain issues. Code coverage doesn’t tell anything about the quality of the tests: covered code only means that the code gets executed during test run, but it doesn’t mean the tests are actually verifying anything in that code. Code coverage report can prove that you’re not testing some code, but even 100% code coverage doesn’t prove that you’re testing everything.

Jest includes code coverage report↗ by default. Otherwise use nyc↗ to generate one.

Codecov↗ and Coveralls↗ collect coverage for every pull request and post a comment explaining how a pull request would affect project coverage. You can require that all, changed in the pull request, lines are covered with tests.

Code Complexity

#

As code evolves, it tends to become more complex. The code will likely end up with hot spots that are fault prone. Understanding where those spots are, and making them simpler, may help to reduce number of issues where it’s the most important.

Tools like complexity-report↗, plato↗, and jscomplex↗ give this type of output. ESLint has specific checks for complexity↗, Iroh↗ performs runtime checks.

Smoke Testing

#

Smoke testing verifies that the vital functionality works in production. The purpose of these tests is to check whether the application might be working or not. They are light to write and can be a starting point if the codebase doesn’t have any tests yet. You could for instance assert that the application runs by logging in and out of the application after production deployment.

Code Size

#

The size of the code can be important especially for frontend packages as you want to minimize the amount of code the client has to download and parse. Tools like size-limit↗ and bundlesize↗ will warn you when your package is growing.

Setting up size-limit

#

You can set up size-limit to fail the CI if your library accidentally grows over a certain limit.

To do that, install size-limit first:

npm install --save-dev size-limit

Add a new script and a size-limit section to your package.json:

"size-limit": [

{

"path": "index.js"

}

],

"scripts": {

"size": "size-limit",

"test": "jest"

}

Run npm run size to see the current size of your library, with all dependencies, minified and gzipped.

Now, set the limit: it’s recommended to add around 1 KB over the current size, so you’ll know about any size increase:

"size-limit": [

{

"limit": "9 KB",

"path": "index.js"

}

]

And finally make the CI fail on size increase:

"scripts": {

"size": "size-limit",

"test": "jest"

"posttest": "size-limit"

}

If the package will ever grow over 9 KB, you’ll see an error like this:

Package size limit has exceeded by 25.57 KB

Package size: 34.57 KB

Size limit: 9 KB

With all dependencies, minified and gzipped

npm run size -- --why.

Design by Contract

#

Design by Contract↗ is a technique that allows you to push invariants, preconditions, and postconditions close to the implementation. The idea can be implemented on code level, but you can also extend the language, as babel-plugin-contracts↗ does.

Conclusion

#

Testing is a complex topic worth understanding. Testing isn’t about developing faster but rather developing in a sustainable way. Tests show their value especially when multiple people work on a project. Tests support development process and allow the team to move faster while avoiding breakage. And even if breakage happens, good practices improve the process to avoid the problems in the future.

The biggest question is what tests to write and when. It’s good to remember testing is a form of risk management. Especially when prototyping, tests won’t provide their maximum value since at this stage you are prepared to throw the code away. But if you are developing long term, the lack of tests begins to cause pain as new requirements appear and the implementation has to evolve to fit the new needs.